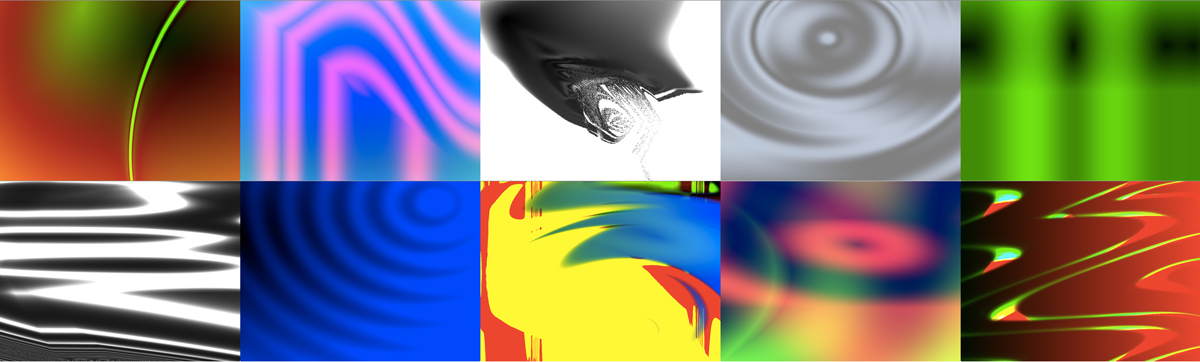

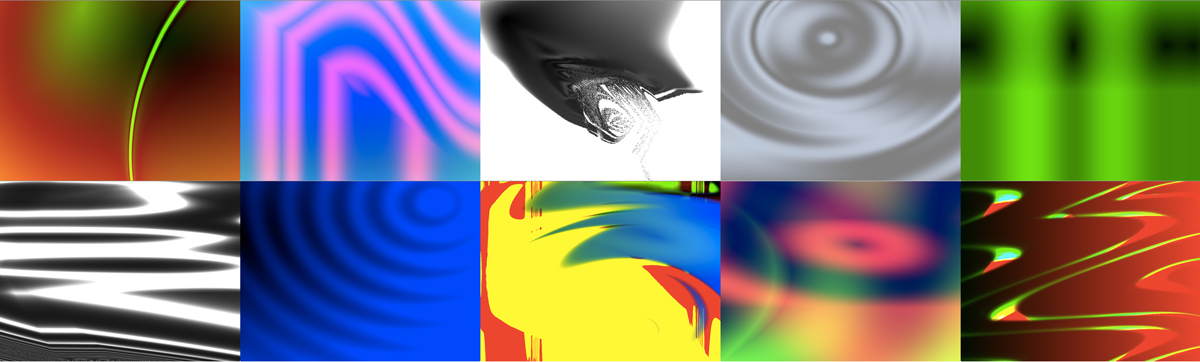

Screenshots of the Audiovisualiser

| Chris Kiefer Department of Informatics, University of Sussex, UK. |

Approximate programming is a novel approach to interacting with code in creative software systems. It merges techniques from live coding, gene expression programming (Ferreira 2001), multiparametric control (Kiefer 2012) and parameter space exploration (Dahlstedt 2009). Code is generated in realtime through a transformation of an array of numbers analogous to a gene in evolutionary programming systems. This gene can be created by a musical controller, allowing the player to interact with code though gesture and motion capture. The gene can also be drawn from other data sources, for example from realtime music information retrieval systems, allowing code to be generated from any computational process.

The system attempts to bring expressive bodily gesture into the process of interacting with code, as an augmentation to the conventional coding editing interfaces typically used for live coding. It aims to do this while preserving code as the primary focus of the system, to harness the flexibility of code, which increasing the involvement of the body in its creation. The system is named approximate programming because the results for a particular gesture or gene are, at least initially, unknown, although the broad domain may be predictable based on knowledge of the gene-to-code mappings. The system is primarily exploratory, although exploration transitions towards repeatable performance as the search space is mapped out by the player.

The development of this technique was motivated by a desire to find ways to express code responsively in 'musical' time. Further details of the background to this project are given in (Kiefer 2014). The author has used the system in performance in two different contexts: for musical performance, and as an autonomous engine for audiovisualisation. Both of these contexts are presented here as case studies of the development of approximate programming techniques. Following this, the strengths and pitfalls of approximate programming are discussed, along with the development of new extensions to address the key limitations of the system.

This work is rooted in the field genetic programming (GP) (Poli, Langdon, and McPhee 2008), and more closely to a variant of GP, gene expression programming (Ferreira 2001), taking the idea of expressing code as a transformation of a vector of numbers and using this vector to explore a large non-linear space of possibilities through a mapping of the gene to a tree representation of the code. The similarities however end with the use of this representation, as evolutionary search techniques are not used in approximate programming. Instead, the space of possibilities is explored in realtime, as the player navigates through the parameter space. The search space can be re-modelled, expanded or restricted by changing the set of component functions on which the transformation draws. This process places the technique as a hybrid of a parametric space exploration system (Dahlstedt 2009, ???) and interactive evolution (Dorin 2001), where a human is at the centre of the search process. Within the field of live coding, approximate programming overlaps with several other projects and pieces. Ixi Lang (Magnusson 2011) has a self-coding feature, where the system runs an agent that automatically writes its own code. D0kt0r0's Daemon.sc piece (Ogbourn 2014) uses a system that generates and edits code to accompany a guitar improvisation. [Sisesta Pealkiri] (Knotts and Allik 2013) use a hybrid of gene expression programming and live coding for sound synthesis and visualisation. McLean et al. (2010) explore the visualisation of code; this is a theme that has emerged as an important issue in approximate programming, where code changes quickly, and robust visualisation techniques are required to aid comprehension by the programmer.

Approximate programming takes two inputs: a numeric vector (the gene) and an array of component functions. It outputs the code for a function built from the component functions, according to the content of the gene. It is embedded within a system that compiles and runs each newly generated function, and seamlessly swaps it with the previously running function as part of a realtime performance or composition system. It should be noted that the use of the term gene here does not imply that an evolutionary search process is used to evolve code, but this term is still used because of the relevance of other genetic program concepts. The component functions are typically low level procedures, including basic mathematical operations, but may also include larger procedures that represent more complex higher level concepts. The algorithm works as follows:

create an empty list of nodes that contain numerical constants, P

choose a component function, C, based on the first element in the gene

find out how many arguments C has

while there are enough gene values left to encode C and its arguments

create a new tree node to represent this function

use the next values in the gene as parameters for the function

add the parameters as leaf nodes of the new tree

add the parameter nodes to the list P

if the tree is empty

add this new tree at the root

else

use the next gene value as an index to choose a node containing a function parameter from P

replace this parameter node with the new tree

remove the parameter node from P

choose a new component function, C, using the next gene value as an index

find out how many arguments C hasBroadly, the algorithm builds a larger function from the component functions by taking constant parameters in the tree and replacing them with parameterised component functions. A SuperCollider implementation of this algorithm is available at https://github.com/chriskiefer/ApproximateProgramming_SC.

The first use of this system was for a live musical performance. The system was built in SuperCollider. During the performance, the component functions were live coded, while the gene was manipulated using a multiparametric gestural controller. This controller output a vector of 48 floating point numbers, at around 25Hz, and these vectors were used as genes to generate code. This is an example of some component functions:

~nodes[\add] = {|a,b| (a+b).wrap(-1,1)}

~nodes[\mul] = {|a,b| (a*b).wrap(-1,1)}

~nodes[\sin] = {|x,y| SinOsc.ar(x.linexp(-1,1,20,20000), y)}

~nodes[\pulse] = {|x,y,z| Pulse.ar(x.linexp(-1,1,20,20000),y, z.linlin(-1,1,0.2,1))}

~nodes[\pwarp] = {|a| Warp1.ar(1,~buf2, Lag.ar(a,10), 1, 0.05, -1, 2, 0, 4)}

~nodes[\imp] = {|a| Impulse.ar(a.linlin(-1,1,0.2,10))}

~nodes[\imp2] = {|a| Impulse.ar(a.linlin(-1,1,3,50))}This example shows a range of functions from low level numerical operations to higher level functions with more complex unit generators. These functions could be added and removed from a list of the current functions that the system was using to generate code. The system generated code that was compiled into a SuperCollider SynthDef. Each new Synth was run on the server and crossfaded over the previous Synth. An example of the generated code is as follows:

~nodes[\add].(

~nodes[\pulse].(

~dc.(0.39973097527027 ),

~nodes[\pulse].(

~nodes[\pwarp].(

~nodes[\pwarp].(

~dc.(0.6711485221982 ))),

~nodes[\pwarp].(

~nodes[\mul].(

~dc.(0.6784074794054 ),

~nodes[\saw].(

~dc.(0.999 ),

~dc.(0.999 )))),

~dc.(0.5935110193491 )),

~dc.(0.39973097527027 )),

~dc.(0.38517681777477 ))A new version of the approximate coding system was developed to create openGL shaders, using GLSL shading language. This system worked in a very similar way to the SuperCollider system; a set of components functions was present in the source of each shader, and a larger scale function was generated from a gene, consisting of calls to these component functions. Visuall, the system took a functional rendering approach; it created pixel shaders, which took a screen position as input and output the colour value for that position. The intention of this system was to create audiovisualisations, and audio was used as input to the approximate coding system in two ways. Firstly, the gene was generated from sections of audio; every bar, an analysis was carried out to generate a new gene from the previous bar of audio. The intention was that similar bars of audio should generate similar visual output, and various combinations of audio features were experimented with for this purpose. Secondly, an MFCC analyser processed the realtime audio stream and streamed its feature vector to the fragment shader; component functions in the approximate coding system drew on this data, so the resulting pixel shader reacted to the textures in the realtime audio stream. The system was fine tuned with a preset library of component functions, and then used for a live performance where it autonomously generated the audiovisualisation. The system was built using OpenFrameworks.

Screenshots of the Audiovisualiser

These two case studies complement each other well as they explore the system in two very different use cases. This demonstrates the flexibility of approximate programming, and also highlights limitations of the system that need to be addressed.

To begin with, I will explore the benefits of using this system. The principle gain from this system is the ability to explore relatively complex algorithms in a very intuitive, bodily way, in stark contrast to the cerebral approach that would be required to generate the same code manually. Furthermore, the process of search and exploration places the programmer/players sensory experience at the forefront of the process, and externalises rather than internalises the creative process. Live coding the component functions provides a mid-point between these two poles, linking programming and sensory exploration. The component functions are interesting as they represent low-level concepts in the search space that are transformed and combined into a higher-level concepts in the output. For example, in the sound synthesis version of the system, if sine wave generators, adders and multipliers are provided as components functions, an FM synthesis type output will be obtained. If impulse generators are added, then rhythmic outputs start to appear. In the graphical version, there is a clear mapping between low-level numerical operations and visual features that appear in the outputs, for example sine generators create circular forms, and euclidean distance functions create colour gradients. The dynamics of programming components and exploring them creates an interesting potential for content creation and performative exploration of complex multi-dimensional search spaces. To further this, the code paradigm is preserved throughout the process, and the performer can examine the resultant code output as part of the exploration. This makes the system transparent to the user, and very malleable as the results are reusable and recyclable.

There are two key limitations of the system that need to be addressed, concerning nonlinearity of the search space and interaction with the code. In case study 1, the resultant code from the approximate programming system was projected to the audience, and was displayed on the computer used for the performance to be used as part of the navigation process. The code was laid out as in the example above, but without colour coding. It was the intention to use this code as part of the reference to exploring the search space, in keeping with the design of the system which places the code form at the forefront of the system. The code however moved very fast (in this case this was partially due to the instability of the controller being used), and without visual augmentations it was difficult to comprehend at the speed it was being presented. It would be ideal if this code could be used as a significant part of the approximate programming process, and so visual augmentations to the output code are a key priority to address. The second issue was most apparent in the audiovisual system, and concerns the nonlinearity of the search space. The intention of the audiovisual system was to generate code based on analysis of sections of music in such a way that similar sections would generate similar audiovisualisations. This worked sometimes, but because of the nonlinearity of the transformation between gene and phenotype, often similar bars would create very different audiovisualisations, implying that the search landscape is far from smooth. Exploring methods for smoothing out this landscape is the second key issue to address with this system, and the most challenging one. Attempts towards addressing the first challenge of increasing engagement with the system output are now presented.

Two new augmentations to the approximate programming system will now be described, that aim to increase potential for engagement with the code output both visually and interactively.

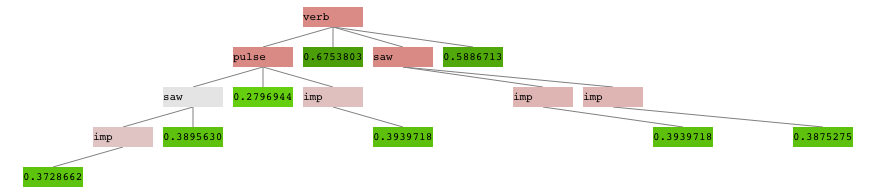

The original presentation of code output by the system was difficult to comprehend - although it had some basic formatting, there were few visual aids, and fast changes were challenging to follow. Showing this output as text was perhaps one step to far in visualising the output, and this new augmentation rewinds the process to the tree representation of the code, before it's converted to text. The logic of the code is still present in this form, but without the trappings of textual syntax it's possible to present a logical process in a simpler way that aids comprehension by the performer. Furthermore, the system at the moment does not have a facility for tracking direct edits to the code output, so there isn't a strong case for viewing it as text anyway.

The new system presents the code tree graphically, as shown in figure 2. It uses two features to enhance comprehension. Firstly, numbers have a dual representation, as text and as a colour mapping on the background of their text box. This allows an easy overview of parameter values. Secondly, significant nonlinearities in the search space are caused when a function placeholder changes to point to a different component function. It's helpful to the player to know when this might happen, so function identifiers are also colour coded; when their underlying numerical value is sitting between two functions, they appear grey. As their underlying value moves in either direction towards a boundary where the function will change, the background is increasingly mixed with red. This gives an indication of when the code is in a more linear state, and also indicates when it's approaching a significant change.

A visualisation of the code tree

The tree in figure 2 corresponds to the code below:

~nodes[\verb].(

~nodes[\pulse].(

~nodes[\saw].(

~nodes[\imp].(

~dc.(0.37286621814966 )),

~dc.(0.38956306421757 )),

~dc.(0.27969442659616 ),

~nodes[\imp].(

~dc.(0.39397183853388 ))),

~dc.(0.67538032865524 ),

~nodes[\saw].(

~nodes[\imp].(

~dc.(0.39397183853388 )),

~nodes[\imp].(

~dc.(0.38752757656574 ))),

~dc.(0.58867131757736 ))Further to aids for visual comprehension of code, the code tree presents an opportunity for the programmer to further interact with the system. A new feature was added augment the code tree through mouse interaction together with gestural control. It works as follows:

The player chooses a point on the code tree with the mouse that they would like to change.

They also choose the size of the gene they will use for this change.

When they click on the node, a new sub-tree is spliced into the main code tree. Now, all editing changes this sub-tree only, and the rest of the tree is kept constant.

The player can use this system to slowly build up code trees, with either fine-grained or coarse adjustments.

The new augmentations clarify code representation, and allow new interactions that give the player more refined control over the system if this is desired. Within this new framework, there's plenty of room to explore new ways to combine code editing from multiple points of interaction: text editing, GUI controls, physical controllers and from computational presses. This new part of the system is work-in-progress, and it currently under evaluation by the author in composition and live performance scenarios.

A new approximate programming system has been presented, which aims to create a hybrid environment for live coding which combines traditional code editing, embodied physical control, GUI style interaction and open connections to realtime computational processes. It has been explored in two case studies, one that used the system for musical improvisation in SuperCollider, and one that ran autonomously creating audiovisualisations using GLSL. The two case studies show that the system, from the authors perspective, has particular strength in enabling embodied control of code, and in augmenting live coding with gestural control. There are two key limitations of the system; challenges in reading and interacting with the final code output that it creates, and the non-linearity of the search space. This paper offers initial solutions to enabling higher quality engagement with code outputs, by presenting the code tree graphically instead of presenting the code in textual form. A further augmentation allows the player to use a GUI to select and edit sections of the tree. These augmentations are currently under evaluation, and future work will explore this area further, along with methods for managing nonlinearity in the search space.

Overall, this project has plenty of research potential in interface design, audio and visual synthesis and performance aesthetics. The author intends to make a future public release to gather more data on how musicians and visual artists would use this type of technology.

Dahlstedt, Palle. 2009. “Dynamic Mapping Strategies for Expressive Synthesis Performance and Improvisation.” In Computer Music Modeling and Retrieval. Genesis of Meaning in Sound and Music: 5th International Symposium, CMMR 2008 Copenhagen, Denmark, May 19-23, 2008 Revised Papers, 227–242. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02518-1_16.

Dorin, Alan. 2001. “Aesthetic Fitness and Artificial Evolution for the Selection of Imagery from the Mythical Infinite Library.” In Advances in Artificial Life, 659–668. Springer.

Ferreira, Cândida. 2001. “Gene Expression Programming: a New Adaptive Algorithm for Solving Problems.” Complex Systems 13 (2): 87–129.

Kiefer, Chris. 2012. “Multiparametric Interfaces for Fine-Grained Control of Digital Music.” PhD thesis, University of Sussex.

———. 2014. “Interacting with Text and Music: Exploring Tangible Augmentations to the Live-Coding Interface.” In International Conference on Live Interfaces.

Knotts, Shelly, and Alo Allik. 2013. “[Sisesta Pealkiri].” Performance, live.code.festival, IMWI, HfM, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Magnusson, Thor. 2011. “Ixi Lang: a SuperCollider Parasite for Live Coding.” In Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference, 503–506. University of Huddersfield.

McLean, Alex, Dave Griffiths, Nick Collins, and G Wiggins. 2010. “Visualisation of Live Code.” In Electronic Visualisation and the Arts.

Ogbourn, David. 2014. “Daem0n.Sc.” Performance, Live Coding and the Body Symposium, University of Sussex.

Poli, Riccardo, William B. Langdon, and Nicholas Freitag McPhee. 2008. A Field Guide to Genetic Programming. Published via http://lulu.com; freely available at http://www.gp-field-guide.org.uk. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1796422.